The Bill Lane Center for the American West, Stanford University

2005 Prize Winning Series

By Jerd Smith and Todd Hartman

Rocky Mountain News, Oct 2, 2004

Two weekends a month, Angela Burdick and Bruce Rindahl flee metro Denver's grime and noise to seek refuge in Colorado's lush high country.

For this couple, and tens of thousands of other Coloradans, the lure of sunshine and a day under sail or on the ski slopes - all less than 100 miles from home - is simply too strong to resist.

But the very ingredient that makes their mountain retreat so magical - the cold clear water that purrs through rock-and-log-strewn streams - is under siege, threatening the high country that is Colorado's postcard to the world.

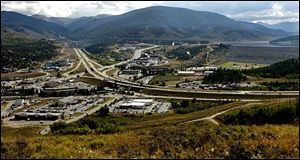

Already, the Front Range takes vast amounts of water from the counties that are home to Winter Park, Keystone, Vail and Aspen.

But now Front Range utilities are reaching for the last of the extensive water claims staked out decades ago in Grand, Summit, Eagle and Pitkin counties. The utilities, including Denver Water, need more to satisfy the demands of ever-growing cities stretching from Fort Collins to Colorado Springs.

Unless new deals are struck between the Front Range and Western Slope, portions of the Fraser, the Blue, the Eagle and the Roaring Fork rivers - the waterways that give birth to the mighty Colorado River - could be mere trickles, or even go dry, for significant periods of the year. The results: stressed fish, stranded kayakers and mountain towns with polluted water and growth caps because they lack sufficient water supplies.

"I think we've all been guilty of believing the water supplies are endless, and they really aren't," said Burdick, a real estate agent keen to the irony of living in an urban area that depends on water from her cherished mountain getaway.

More and more, mountain residents will be forced to compete with the Front Range for the last trickles of Western Slope headwaters.

New studies predict that Grand and Summit counties will run short of water in 25 years. And officials in Eagle and Pitkin counties also foresee problems with water quantity and quality if Front Range utilities draw more from the Eagle and Roaring Fork rivers.

All this threatens the streams that have thrilled rafters, attracted anglers, made snow for skiers and fueled the economic boom brought by the second homes peppering Colorado's resort towns.

These fast-growing regions need more water for themselves, but the bigger drain comes from cities such as Denver, Colorado Springs and Fort Collins as they look for ways to satisfy the thirst of a projected 2 million new Front Range residents by 2030.

Thanks to a five-year drought, Western Slope locals see the cruel twist: mountain towns that spend winter knee-deep in snow must take steps to slow growth or limit water use because the Front Range has first dibs on most of the resource.

Even when the drought eases and the state returns to years of average precipitation, headwater communities could find themselves water-starved.

"It's a hard reality, but the water is owned by these cities, and they are going to bring it over," said Rindahl, a water engineer and Front Range resident who has spent much of the past 20 years seeking refuge in Colorado's high country.

The impacts are expected to be severe:

-

In Grand County, water taps are being rationed because Winter Park doesn't have enough water for development. At the same time, Denver Water and the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District are hoping to pull enough additional water from Grand County for a total of 80,000 homes.

-

In Summit County over the next 12 to 24 years, Denver plans to boost by 77 percent the amount of water it collects from the Blue River. That will cause water levels to fluctuate dramatically at Dillon Reservoir, a recreation spot cherished by boaters and water skiers.

-

In Pitkin County, portions of the Roaring Fork in a popular riverside park in Aspen could go dry if Colorado Springs, Pueblo and Arkansas Valley farmers succeed in diverting more water through the Twin Lakes Tunnel.

-

In Eagle County, Aurora and Colorado Springs plan to nearly double the amount of water they're taking from the Eagle River. At the same time, Eagle County hopes to partner with Denver to build a major reservoir that would benefit the county and the Front Range.

Why the push for high country water? Why not tap the vast amounts of Colorado water used for farming? Or recycle more treated wastewater and drink it, instead of just irrigating parks and golf courses with it? Why not emphasize greater conservation?

Experts and utilities consider all those as potential sources for satisfying some of the expected new demand.

But it's the crisp, clear headwaters of the mountain counties that everyone covets.

"The fight up there is over the good water," said David Robbins, a Denver water attorney who can be found most weekends in his Summit County home.

That "good water" from the mountaintops is so named because it's comparatively clean, requires little treatment and lies close to vast water collection systems owned and operated by the cities.

"The headwaters are the most valuable (supplies) we have," said Neil Grigg, a water historian, author and Colorado State University engineering professor. "It doesn't make sense to de-water them too much.

"Economically, they're valuable because they're high up, and their diversion points are close by. Ecologically, they're important because they help sustain the whole ecosystem of the Colorado River.

"We've reached a critical balancing point," Grigg said. "(As a state) we're going to have to make some tough decisions."

Prospecting for waterIn Colorado, there is an intimate connection between the water that city dwellers consume and the state's hallmark snow-covered mountains, where 80 percent of the state's drinking water is derived.

Diverting water from the once-remote mountain counties began in the last decades of the 1800s, when surveyors and water prospectors hiked the Never Summer Range in Grand County, the Ten Mile in Summit, the Holy Cross in Eagle and the Collegiate Peaks in Pitkin.

Back then, when fewer than 500,000 people populated the state, it was unlikely anyone envisioned that Colorado would one day be home to more than 4.3 million people.

To early water prospectors, the mountain streams' water supplies seemed eternal, finding new life with each spring snowmelt. Front Range cities drew freely on these supplies and made legal claims for more in the future - with few angry locals or environmental laws standing in their way.

The picture is much different now. With Colorado's population expected to reach 7 million by 2030, the limits of these once-bountiful streams are being tested, the last drop of their supplies in sight.

Increasingly, the water that keeps trout streams cool and clear, allows kayak courses to roar through Vail and Breckenridge, and fuels thousands of acres of snowmaking at ski resorts will be diverted to the Front Range.

"The Front Range is killing us," said Lane Wyatt, a water specialist with the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments. "But in a way, they are us."

Throughout the headwater counties, local officials are scrambling to capture what little is left of available water supplies while pressuring Front Range cities to share some here, store some there and leave as much in the streams as possible.

At odds are a $3 billion mountain tourist economy whose core asset is water and an urban corridor with the political clout and the cash to simply take the water if compromises can't be made - even if taking it damages the wild places and weekend playgrounds that draw many to Colorado in the first place.

"People on the Front Range think water starts at their kitchen tap," said Scott Hummer, the top water cop on the Blue River. "But they're wrong. It ends there. Sometimes I just want to tell them, 'It's the same water.'"

Exploding mountain growthIt isn't simply Front Range growth testing these clear waters.

The counties' own populations have doubled in the past 50 years and are projected to double again by 2030, according to Colorado's state demographer.

Water demand for skiing and recreation is also straining supplies.

Making one acre of snow for a ski slope, for instance, requires 326,000 gallons of water a year, according to Vail Associates. That's enough to supply up to two Denver homes for a year.

Keeping the Vail kayak course afloat for 12 hours requires 130.4 million gallons of water, enough to keep about 800 homes in lawn water and showers for a year.

By 2030 each of the headwater counties will need about twice as much water as they use now, according to new data from the $2.7 million Statewide Water Supply Initiative. Many mountain communities are just beginning to realize how little water they really own, thanks to water deals made decades ago.

Those early mass water claims - perfectly legal under Colorado water law - mean that nearly half of the natural flows in these rivers' headwaters are already moving to Front Range cities, according to the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments.

By 2030 that number will rise significantly.

In Summit County's Blue River, for instance, about 25 percent of the headwaters are diverted. That figure will rise to about 50 percent as Denver delivers new supplies through Dillon Reservoir and the Roberts Tunnel.

In Grand County, the Fraser River loses more than 60 percent of its flows to Denver Water and the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, which serves Fort Collins, Greeley, Loveland, Lafayette, Broomfield and part of Boulder.

In 25 years, more than 80 percent of the Fraser's flows will come to the Front Range, according to new studies.

"There's reason for alarm at this point," said Grand County Commissioner James Newberry.

In response, environmental coalitions are re-forming, anticipating new battles for water project permits. Citizen groups hold monthly water education sessions in the Eagle Public Library at Avon.

Heated negotiations are under way almost weekly as Denver, Aurora, Fort Collins and Colorado Springs push to launch the last wave of diversions while keeping their powerful Western Slope counterparts happy.

This year alone, Denver Water and the Northern water district are devoting nearly $2 million to their high-country planning efforts.

"Our interests and the interests of the Western Slope are never going to be the same," said Ed Pokorney, director of planning at Denver Water, Colorado's largest municipal water supplier. "And they shouldn't be. They don't have to go to bed every night worrying about supplying water to 1.2 million people (Denver Water's customer base)."

The pressure on both sides is so fierce that Denver and other utilities - once used to taking the water with little interference - are eyeing agreements to give up blocks of undeveloped water rights and defer to local needs and environmental concerns. In exchange, the utilities hope to get at least some water immediately while avoiding the threat of lengthy legal action that could throttle their efforts to meet customer demand.

New coalitionsPartnerships deemed unthinkable even 15 years ago are beginning to emerge. Vail Associates, for instance, is working with Aurora and Denver to see whether maybe, just maybe, Eagle County and the Front Range might share the costs and benefits of a planned reservoir at Wolcott.

The Northern water district - the state's largest mover of water from west to east - argues that it's already given plenty to the West Slope over the years in exchange for water, including $10 million in the 1980s to help build a reservoir.

Even so, Northern won't rule out giving up more to complete efforts at moving another 30,000 acre-feet in the coming years. It already takes 230,000 acre-feet - enough for 460,000 homes.

"Have we closed and locked the door for further discussion?" said Brian Werner, spokesman for Northern. "No, we're willing to talk."

Denver Water - historically the king on the state's water chess board - also operates under a new mandate to cooperate. That change began after the expensive defeat of its bitterly opposed Two Forks dam 15 years ago and continues with Denver Mayor John Hickenlooper's focus on regional solutions.

But it isn't easy.

"We have a lot of issues in dispute and in common with those counties," said Denise Maes, a Denver Water Board member and past president. "I have to figure out how to get (new supplies for Denver) without p------ the rest of the state off. It's daunting. But we are not going to simply go get water and say, 'Hey, we love ya, but you're on your own.' That's not what we're about, and that's not what we're going to do."

Such words don't deliver much comfort to Western Slope water officials who have heard the language of compromise turn tough in negotiations.

After a long summer of meetings, Taylor Hawes, an attorney with the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments, said relationships had been strained almost to the breaking point.

"I've never seen it this tense."

Five-Part Series List | continue to part 2

Five-Part Series List | continue to part 2

Texas Tribune, ProPublica

The Desert Sun and USA Today

CPI, InsideClimate News, The Weather Channel

The Seattle Times

The Sacramento Bee

High Country News

5280 Magazine

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

What Went Wrong?

The Seattle Times

San Antonio Express-News

The Los Angeles Times

High Country News