The Bill Lane Center for the American West, Stanford University

2013 Knight-Risser Prize Symposium

Technology and Up-Close Reporting Help Environmental Stories Make a Difference

John S. Knight Fellowships

If journalists want their environmental stories to make a real difference, it may not be enough to just conduct research and interviews and publish. Today’s audiences need to identify with the issue – to visualize it, even experience it – in a personal way.

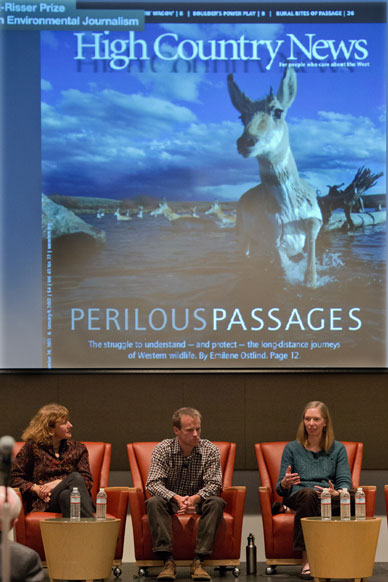

That’s what writer Emilene Ostlind and photographer Joe Riis were able to do with “Perilous Passages,” their two-year project on pronghorn antelope migration in Wyoming. It won the 2012 Knight-Risser Prize for Western Environmental Journalism. And it encouraged changes, big and small, to keep this ancient migration path, one of the longest in the western hemisphere, safe for its four-legged travelers. Wireless photography tools and immersive fieldwork made it possible.

The use of technology in wildlife journalism was the topic of the Knight-Risser Prize Symposium at Stanford, at which the annual journalism prize is presented. The Knight-Risser Prize, which also comes with a $5,000 award, recognizes the best environmental reporting on the North American West — from Canada through the United States to Mexico. They symposium explores new ways to ensure that such sophisticated environmental reporting survives.

The discussion, moderated by photographer and John S. Knight Journalism Fellow Samaruddin Stewart, included the two prize winners, Philippe Cohen, executive director of Stanford’s Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve, and Susan McConnell, a nature photographer and Stanford biology professor.

Complete Video of the Symposium (Story continues below)

A Personal Story

Ostlind went out backpacking to find the pronghorn’s path, later detailing her challenges along with that of the pronghorns’. “She got lost in drainages, battled through thick brush, and post-holed her way through deep snow,” said Paul Larmer, executive director of High Country News, where her story was published. She alerted Riis about good observation locations. He then went out to place cameras with remote triggers. During subsequent migrations, the cameras captured unprecedented video and close-ups of the antelopes fording rivers, cleaving willow thickets and maneuvering housing developments, highways and natural gas fields.

“We’re being brought closer to the lives of these organisms,” said Cohen. “It helps us understand systems in ways we never could” and perhaps affect policies for managing development and wildlife.

Said McConnell: “Stephen J. Gould, the champion of biodiversity, said that we will not fight to preserve what we do not love. What they’ve done so successfully in this story, through words and images, we start to feel connected to these animals. … And if we care, we might act.”

The now-affordable remote triggers were invaluable to the pronghorn project, but they needed the journalist’s guiding hand. The infrared beams that start cameras rolling when crossed only have a three-foot wide range. The first image from a camera set up at the five-mile-wide Green River crossing was “too blurry and had too much land in it,” said Riis. He moved the camera to show more of the river. The result had “no feel to it.” He then moved the camera down into the water. The first photos showed only two bucks – hardly a migration. Another had more animals but poor lighting.

Patience Pays Off

But near the end of two and a half months – bingo. A determined-looking doe is seen in close-up with a trail of pronghorn behind her. Vivid lighting paints her shadow on the rock she’s passing. It was, said Riis, “a shot worth two and a half years of working on the project.”

Panelists at the Knight-Risser Prize Symposium, from left to right, are Philippe Cohen, Susan McConnell, Joe Riis and Emilene Ostlind. On the far right is moderator Sam Stewart. Photo: Steve Castillo

“Getting within three feet of the track is a real coup,” said McConnell, a teacher of conservation photography. But, more than that, it “gives us a sense of being in her world, at her feet. The light and splash of water, the landscape, the clouds — it has everything you would want to bring us into a story.” So, too, she said, Ostlind’s direct observations, woven with scientific information, created a “personal journey that made us feel part of the story.”

“It’s pretty hard to save or conserve a place if you can’t visualize what you’re trying to conserve,” said Riis.

Camera trap technology is increasingly being used to better understand the natural environment. Cohen said he and several graduate students, working with the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, were able to learn something about a mountain lions in the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve, five miles west of campus.

“We were able to see how often they came through the preserve and the impact of people coming through the preserve,” he said. “What we found is that the lions were adjusting and trying to avoid people. ”

A video visualization of the flight of a stork embedded with a GPS chip offered another example of what technology, combined with human observation, can tell us. High above a rectangular field, a white line moved back and forth, creating a coiled string atop the green. Why was the bird making this strange loop? Ground observation found it was following of a tractor that was unearthing insects as it plowed the field.

Publish and Present

Ostlind and Riis spent two years – four migration seasons – tracking the 300 to 400 pronghorn that travel 170 miles between Grand Teton National Park and Wyoming’s Upper Green Valley to escape deep snow, find food and give birth. Only about a quarter of the path is safe from development – the 45 miles in U.S. Forest Service land now under federal protection. The rest includes highway crossings, gas drilling projects, residential subdivisions and a 9,100-foot mountain pass.

They published their story, then went to schools, libraries, community centers and Bureau of Land Management offices to make personal presentations.

Ostlind didn’t claim direct cause and effect, but she said their stories and outreach brought a lot of attention to the migration. It may have helped contribute to the evidence that the public cared. That’s something the Wyoming Department of Transportation needed, among other things, to justify the $10 million cost of building two wildlife overpasses and six underpasses at the increasingly busy section of Highway 189/191 near natural gas fields where auto-animal accidents have been frequent.

In addition, a local land trust raised funds to retrofit fences along the path with no barbs and a 16-inch bottom space, enough for the pronghorn to crawl under. And individual property owners, who may not have even realized they were on the path, have begun to do things like leave fence gates open during migration season, Ostlind said.

“It’s a part of the state that’s seeing a huge population boom,” people coming to work in the natural gas fields. “But once they understand there is a migration happening, there are small things people can do to help.”

Making a Difference

It’s still stressful on the animals, Riis noted, and it’s unclear how much development the pronghorn path can take. But there’s satisfaction in making some difference.

“One thing that’s been very rewarding is to talk to people who live in the middle of the corridor. They work in the middle of the day and didn’t know the animals were there. The pronghorn may cross through for five minutes and be gone. “It’s been rewarding to help people understand what they have right in their back yard.”

Stories such as theirs “might help us get a sense that we share this place with other organisms,” Cohen said. “We all suffer a certain detachment we need to deal with.”

Mary Ellen Hannibal and Cally Carswell, who contributed stories to the special report “Perilous Passages,” were also winners. James Risser, for whom the prize is named, was on hand to give winners their awards. He is a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and director emeritus of the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships at Stanford.

The Knight-Risser Prize, which also comes with a $5,000 award, recognizes the best environmental reporting on the North American West — from Canada through the United States to Mexico. The symposium brings journalists, researchers, scholars and policy makers together with public audiences. The prize and symposium are co-sponsored by the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships and the Bill Lane Center for the American West, with support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Judges for the prize were Jim Bruggers, environment writer, Louisville Courier-Journal and former president of the Society of Environmental Journalists; Beth Daley, environment writer, The Boston Globe and a 2012 Knight Fellow; Raul Ramirez, executive director of news and public affairs, KQED Public Radio; and Bud Ward, editor, Yale Forum on Climate Change and the Media.

Complete Audio: Knight-Risser Symposium, Feb. 20, 2013

Duration: 1 hour, 7 minutes (download as podcast)

For More Information

Read the 2012 Knight-Risser Prize winning story, "Perilous Passages" and learn more about the winners, Emilene Ostlind and Joe Riis.

Knight-Risser Prize Symposiums:

“When the Well Runs Dry: Confronting a Groundwater Crisis”

January 2017 Knight-Risser Prize Symposium, January 25, 2017

“Breathless in Texas: Energy Production Puts Air at Risk”

2016 Knight-Risser Prize Symposium, February 17, 2016

“Troubled Waters: Marine Life and the Threat of Ocean Acidification”

2015 Knight-Risser Prize Symposium, February 25, 2015

“Deadly Measures: Uncovering a Little-Known Agency's Toll on Wildlife”

2014 Knight-Risser Prize Symposium, February 5, 2014

“Wildlife, Wired: How Technology Is Changing Nature Reporting”

2013 Knight-Risser Prize Symposium, February 20, 2013

“Adapting to Dry Times: The Role of the Media in an Increasingly Arid West ”

2012 Knight-Risser Prize Symposium, January 25, 2012

“The Crisis in Western Environmental Journalism”

November 2010 Knight-Risser Prize Symposium, November 17, 2010

“Visualizing the Environment”

January 2010 Risser Prize Symposium, January 27, 2010

“Climate Change Hits Home”

December 2008 Risser Prize Symposium, December 3, 2008

“Environmental Fallout of the Cold War”

March 2008 Risser Prize Symposium, March 13, 2008

“Water in the West: 21st Century Challenges in a 19th Century Legal Framework”

2005 Risser Prize Symposium, November 1, 2005

Ostlind and Riis spent two years – four migration seasons – tracking the 300 to 400 pronghorn that travel 170 miles between Grand Teton National Park and Wyoming’s Upper Green Valley to escape deep snow, find food and give birth.

“It‘s pretty hard to save or conserve a place if you cant‘t visualize what yout‘re trying to conserve.”

Texas Tribune, ProPublica

The Desert Sun and USA Today

CPI, InsideClimate News, The Weather Channel

The Seattle Times

The Sacramento Bee

High Country News

5280 Magazine

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

What Went Wrong?

The Seattle Times

San Antonio Express-News

The Los Angeles Times

High Country News