The Bill Lane Center for the American West, Stanford University

2011 Knight-Risser Prize Winner Hits “Holy Grail” of Explanatory Journalism

"Dry Times," a comprehensive report in Denver's 5280 magazine on state water shortages, is the winner of the 2011 Knight-Risser Prize for Western Environmental Journalism. The authors, Natasha Gardner and Patrick Doyle, will receive $5,000 at The Knight-Risser Prize Symposium on January 25, 2012 at Stanford University. The symposium will be dedicated to the topic of western water issues.

Prize judges also gave Special Citations of recognition to David Wolman for "Accidental Wilderness," published in High Country News, and Julia Scott, Sasha Khokha and Christopher Beaver for "Nitrate Contamination Spreading in California Communities," distributed by KQED Radio and California Watch.

The six-year-old prize and symposium has just earned a permanent endowment through a challenge grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Prize sponsors, the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships and the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford, raised $100,000 to secure the $200,000 match grant. The funds will support the Knight-Risser Prize program, which is dedicated to promoting sophisticated reporting about environmental issues affecting the North American West.

Contest judges were Christy George, former president of the Society of Environmental Journalists; Mark Trahant, who blogs on Trahant Reports and is former editorial page editor of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Lewis Kamb, a reporter for The (Tacoma) News Tribune and 2010 Knight-Risser Prize winner; and Jeffrey Koseff, faculty co-director at the Woods Institute for for the Environment at Stanford University.

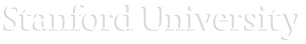

Dry Times explores and explains Denver's water challenges through engaging text and imaginative graphics. It was selected winner for its clear and compelling presentation of a many-layered story of geography, history, land use and policy.

Judges felt Dry Times hit the Holy Grail of explanatory journalism — making a complex and potentially dull topic easy to grasp and fun to read.

The piece "excited me about the subject," said George. "A lot of people could read this and get this. It's a huge mass of stuff. I was kind of blown away."

Trahant said, "People will probably retain more from Dry Times … which makes it more effective."

The package also won high marks from some of the experts, who found nothing had been neglected in its bid for simplicity.

"In 12 short pages loaded with great graphics, the folks at 5280 managed to take a subject that only wonks can love, and make it understandable by the common person," said Bradley Udall, a story source and director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Western Water Assessment, which is based at Colorado University.

"From agriculture to aging infrastructure, climate change to contamination, dishwashers to dams, and even recreation to re-use, the article conveys the multiple interactions and difficult trade-offs inherent in managing this precious and limited resource," he said.

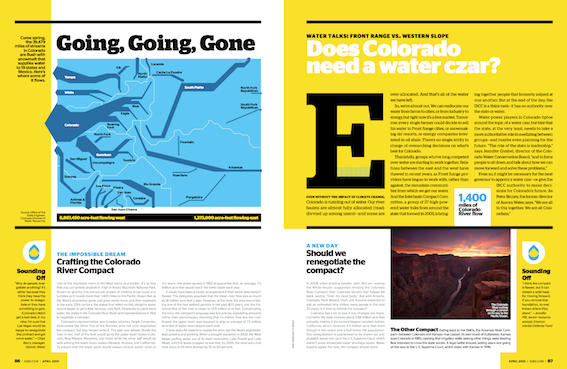

Colorado is a state whose population growth and water supplies are on a collision course. In 20 years, water users could drain the state's streams and wells. Long-held pacts set water allocations within Colorado and to other states. Business, residents, farmers and recreational users all have a stake. Throw in a geography that makes delivery expensive and the unknowns of climate change and you have a tangle of seemingly intractable complications.

But Dry Times' graphics, lively layout and conversational language offer an easy-to-follow path through competing demands, complicated deals and water resources under pressure.

Doyle and Gardner were working separately on environmental stories when they realized collaboration would have more impact. They spent a year sorting through statistics and interviewing experts as well as water users, hoping some aspect of the problem would emerge as their story. In the end, they decided they had to tackle the whole thing.

"Water is a key topic in Colorado. You can't go to a city council meeting without the issue coming up. People fight, argue, theorize and have all kinds of conversations around the issues," said Gardner. "You can't talk about policy without talking about the personal."

Another challenge was their readership. On one end are the water lawyers and scientists "who can be prickly if they think something is being dumbed-down," said Doyle. On the other are "people who turn on their tap and don't know where the water comes from or keep their lawns bright green, even in the summer," said Gardner.

Their goal was to produce a report that was in-depth as well as "dynamic and engaging to readers who are not experts," said Doyle. "Statistics about rainfall or how many water acres are in a reservoir don't mean a lot to the vast majority of people. We wanted to make that approachable."

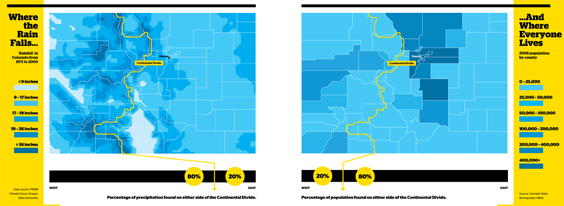

Two graphics show where the rain falls and where people live: Denver straddles the Rocky Mountains. Most of the snowmelt flows west. Most of its population is to the east. The extraordinary time, energy and money it takes to move water to the population is just one of the significant hurdles to meeting water needs.

Detail from "Dry Times" layout in 5280 magazine.

Detail from "Dry Times" layout in 5280 magazine.

Making the issues clear to water users in a state where the "vast majority of people have stereotypical lawns" was critical, said Doyle. More than half the average Denver family's water use is for landscaping, another graphic showed. It also offered five ways to cut home water use.

Lush lawns are "what people are used to; Colorado is a state of transplants," Doyle said, where just about everyone waters their lawns. "What does that say, that you can't have a lawn without some kind of intervention? Maybe lawns are not really proper in this environment."

Judging by readers' responses, their stories, published in April 2010, had an effect, Gardner said. "Teachers still ask for PDFs to distribute to their classes. And we continue to hear feedback from residents that 'this is something we can do right now to cut our water use.' "

And the experts? "We heard more from them about how we made it understandable," she said.

The Knight-Risser Prize for Western Environmental Journalism is a joint venture of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships at Stanford and the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford.

The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation supports transformational ideas that promote quality journalism, advance media innovation, engage communities and foster the arts. The foundation believes that democracy thrives when people and communities are informed and engaged.

The John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships is an ambitious catalyst for journalism innovation, entrepreneurship and leadership. Fellows spend their year absorbing knowledge, honing skills and developing journalism prototypes. They leverage the resources of a great university and Silicon Valley while learning from rich interactions with journalists from around the world.

The Bill Lane Center for the American West is dedicated to advancing scholarly and public understanding of the past, present, and future of western North America. The Center supports research, teaching, and reporting about western land and life in the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

“In 12 short pages loaded with great graphics, the folks at 5280 managed to take a subject that only wonks can love, and make it understandable by the common person,” said Bradley Udall, a story source and director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Western Water Assessment, which is based at Colorado University.

Texas Tribune, ProPublica

The Desert Sun and USA Today

CPI, InsideClimate News, The Weather Channel

The Seattle Times

The Sacramento Bee

High Country News

5280 Magazine

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

What Went Wrong?

The Seattle Times

San Antonio Express-News

The Los Angeles Times

High Country News