The Bill Lane Center for the American West, Stanford University

Investigation into Fracking and Air Pollution Wins 2015 Knight-Risser Prize

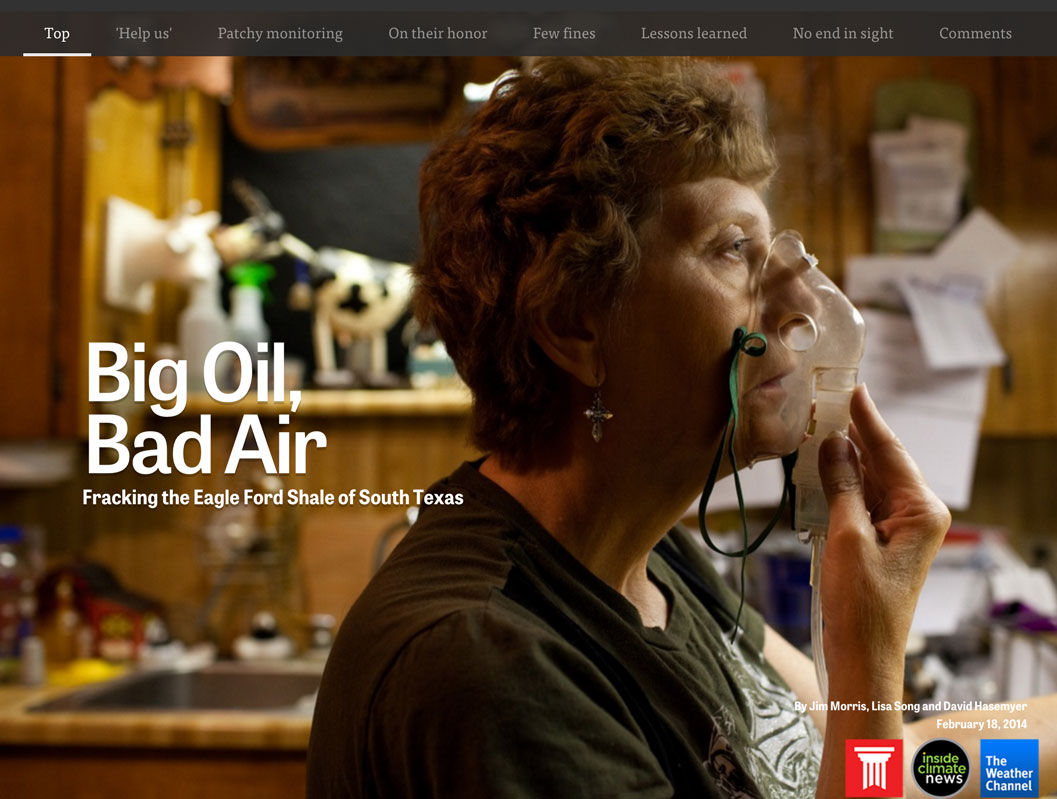

“Big Oil, Bad Air: Fracking the Eagle Ford Shale of South Texas,” a joint reporting project by the Center for Public Integrity, InsideClimate News and The Weather Channel, has been named winner of the 2015 Knight-Risser Prize for Western Environmental Journalism.

Special Recognition Citation

“Warehouse Empire,” by Jessica Garrison of BuzzFeed News, received a Special Citation for its report about the impact of warehouse sprawl at the eastern edge of the Los Angeles Basin.

The Knight-Risser Prize recognizes the best environmental reporting on the North American West — from Canada through the United States to Mexico.

The prize includes a cash award of $5,000, and the winner participates in the annual Knight-Risser Prize Symposium, which brings journalists, researchers, scholars and policy makers together with public audiences to explore new ways to ensure that sophisticated environmental reporting survives in the West. The symposium will be held at Stanford University on February 17. Free registration for the event and reception is open until February 11.

The Winning Entry: “Big Oil, Bad Air”

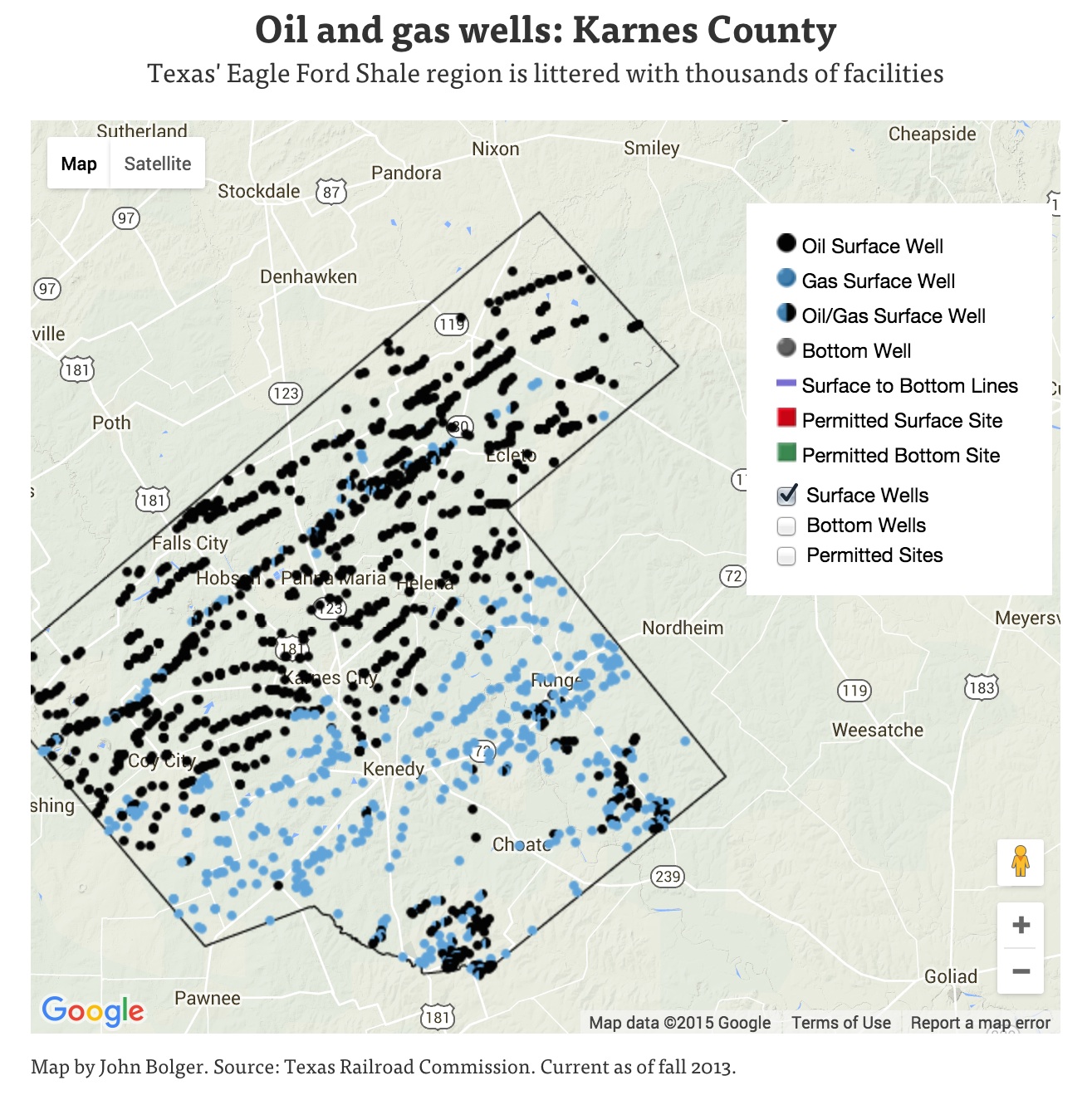

A 20-month joint reporting project spanning three organizations, “Big Oil, Bad Air” explores the tension between cheap energy and air quality in one of the most active oil and gas fields in the United States. The stories focus on 20,000 square miles of Texas where thousands of production facilities, and waste dumped into open pits, release toxic chemicals into the air with virtually no regulatory oversight.

The core project team comprised reporters Jim Morris of the Center for Public Integrity and Lisa Song and David Hasemyer of InsideClimate News; and Susan White, former executive editor of InsideClimate News. Greg Gilderman, a producer with The Weather Channel joined the effort as a video partner.

Read a summary of the 2016 Knight Risser Prize Symposium with photos and complete audio and video here.

Read a summary of the 2016 Knight Risser Prize Symposium with photos and complete audio and video here.

Together, with a dozen more journalists eventually involved, they produced 42 stories and three mini-documentaries, filed more than 50 open-records requests, reviewed thousands of pages of documents, conducted hundreds of interviews and collectively took 12 trips to Texas, Louisiana and Pennsylvania.

Morris, a managing editor at the Center for Public Integrity who has been writing about the environment and worker safety issues for about 37 years, said what gave the project such breadth and texture was the diversity of talent working on it.

“It involved people with TV backgrounds, science backgrounds, traditional newspaper guys like me and David Hasemyer, and an interesting blend of people – younger and older, tech-savvy and not tech-savvy, in my case, sharp graphics people,” he said.

“It took the best of everyone’s skills. And I think the product is better than if any one of the three outlets had done it alone.”

Special Citation to BuzzFeed News

The judges also awarded a Special Citation to Jessica Garrison of BuzzFeed News, for “Warehouse Empire,” a report about the impact of warehouse sprawl at the eastern edge of the Los Angeles Basin. The judges said that it broke ground on an old story – air pollution – in a new and compelling way. One judge said that Garrison took what is a daily fact of American consumer life – “we want stuff that day and cheap” — and connected it to the uncontrolled sprawl of shipping warehouses in the region where Los Angeles, Riverside and San Bernardino counties meet.

About the Prize and the Judging

The Knight-Risser Prize is named for James Risser, two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and director emeritus of the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships at Stanford. It is co-sponsored by the JSK Fellowships and The Bill Lane Center for the American West, with an endowment from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

The Knight-Risser Prize judging panel included Duncan McCue, a reporter for CBC News in Vancouver and a former JSK Fellow, Craig Welch, an environmental writer for National Geographic and co-winner of the 2014 Knight-Risser Prize, Deborah Blum, the director of the Knight Science Journalism program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Felicity Barringer, former national environmental correspondent for The New York Times.

The Cost of a Rush to Riches in South Texas

“Big Oil, Bad Air” exposes the rush to oil and gas riches at the peril of the environment in a 400-by-50-mile stretch of South Texas called the Eagle Ford Shale. It contains vast amounts of oil- and gas-laden sedimentary rock that through hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” is bringing wealth to states like Pennsylvania, Colorado, and North Dakota as well as Texas.

Powerful forces are at work. The shale gas revolution has helped make the United States nearly energy independent. Texas is one of the nation’s biggest producers. What happens there has implications for other oil- and gas-rich states.

“The impacts of rapidly expanded fracking is very much a story for our times,” said McCue.

Judges praised “Big Oil, Bad Air” as a thorough examination of a particularly complex subject – toxic air emissions from oil and gas production. They felt its extensive multimedia presentation made it accessible and of interest to audiences on multiple fronts. And it showed the power of media collaborations on such important topics.

The stories got results:

- Officials will install the first air pollution monitor in an area of intense drilling;

- A Pennsylvania congressman launched an investigation into how states regulate the disposal of oil and gas waste;

- A Texas prosecutor is exploring a possible criminal inquiry—supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency — into allegations by two former state oil and gas inspectors who claim they were fired for being too tough on the industry;

- A group of public-interest health scientists is organizing to challenge the credibility of an influential, industry-friendly consulting firm that advises the state commission on environment quality.

In economically depressed, rural areas like Eagle Ford, hydraulic fracking of deeply buried shale to extract oil and gas promises a new prosperity. But that new wealth has a price, paid more heavily by those who live closest to the wells.

Pro-oil politics has allowed the drilling of 7,000 oil and gas wells and the easy approval of 5,500 more in Eagle Ford, the project reports. Residents complain of respiratory ailments, but there is scant data to substantiate a connection to the wells. How pollution from gas and oil production in Eagle Ford is being measured, monitored and mediated is at the crux of “Big Oil, Bad Air.’’ And the determining forces are money and politics – both local and global.

“The story examined everything – a roll back of regulations, lax rules, political contributions, cronyism,” said Welch. “It looked at risks to human health, but did not overtly claim connections that didn't exist. In fact, the stories were strong, in part because they didn't attempt to draw conclusions from the lack of data, but, rather, made the lack of data the point.“

The investigation digs deep into the political influences and decisions from local to state levels that have left many of the people most directly affected by the wells feeling victimized and abandoned. It shows a loose system of self-auditing by producers that has left the state virtually ignorant of even the true number of facilities operating in Eagle Ford.

“They did a great job of making clear that the questions residents and homeowners have about their own health is just not a priority for the state, which just keeps saying 'Go, go, go' to more oil development,” said Welch. “The West needs more deep-dive environmental journalism like this.”

The unique partnership – two nonprofits and a television channel – originated when Morris identified a story he felt needed more than the resources of his own organization, the Center for Public Integrity.

Morris had read countless fracking stories over the years. Most had to do with groundwater contamination. “Having written a lot of stories about air pollution in Texas and California over the years, it occurred to me there was a big hole in the coverage – air emissions.”

And he knew about the Eagle Ford Shale; he had worked at several Texas newspapers, including the Houston Chronicle.

Morris reached out and suggested a collaboration with InsideClimate News. He’d heard good things about White, the executive editor. She agreed and subsequently brought the Weather Channel on board, he said.

“When Jim called, I jumped at the opportunity,” said White, who is launching an investigative news startup with individual websites focused on three specific issues each year. “I knew enough to know that the public needed more information –– and by combining forces, InsideClimate News and CPI were able to give it to them. The collaboration was as good as it gets.”

The Knight-Risser Prize will be awarded at a symposium at Stanford on February 17. The event will bring together journalists, researchers, policymakers, advocates, students, and the public to explore the environmental issues raised by the winning entry. The prize is co-sponsored by the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships and the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford, with support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

The Knight-Risser Prize for Western Environmental Journalism is a joint venture of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships at Stanford and the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford.

The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation supports transformational ideas that promote quality journalism, advance media innovation, engage communities and foster the arts. The foundation believes that democracy thrives when people and communities are informed and engaged.

The John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships is an ambitious catalyst for journalism innovation, entrepreneurship and leadership. Fellows spend their year absorbing knowledge, honing skills and developing journalism prototypes. They leverage the resources of a great university and Silicon Valley while learning from rich interactions with journalists from around the world.

The Bill Lane Center for the American West is dedicated to advancing scholarly and public understanding of the past, present, and future of western North America. The Center supports research, teaching, and reporting about western land and life in the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Together, with a dozen more journalists eventually involved, they produced 42 stories and three mini-documentaries, filed more than 50 open-records requests, reviewed thousands of pages of documents, conducted hundreds of interviews and collectively took 12 trips to Texas, Louisiana and Pennsylvania.

Click to enlarge

“The story examined everything – a roll back of regulations, lax rules, political contributions, cronyism,” said Welch. “It looked at risks to human health, but did not overtly claim connections that didn't exist. In fact, the stories were strong, in part because they didn't attempt to draw conclusions from the lack of data, but, rather, made the lack of data the point.”

Craig Welch, on Judging “Big Oil, Bad Air”

Texas Tribune, ProPublica

The Desert Sun and USA Today

CPI, InsideClimate News, The Weather Channel

The Seattle Times

The Sacramento Bee

High Country News

5280 Magazine

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

What Went Wrong?

The Seattle Times

San Antonio Express-News

The Los Angeles Times

High Country News